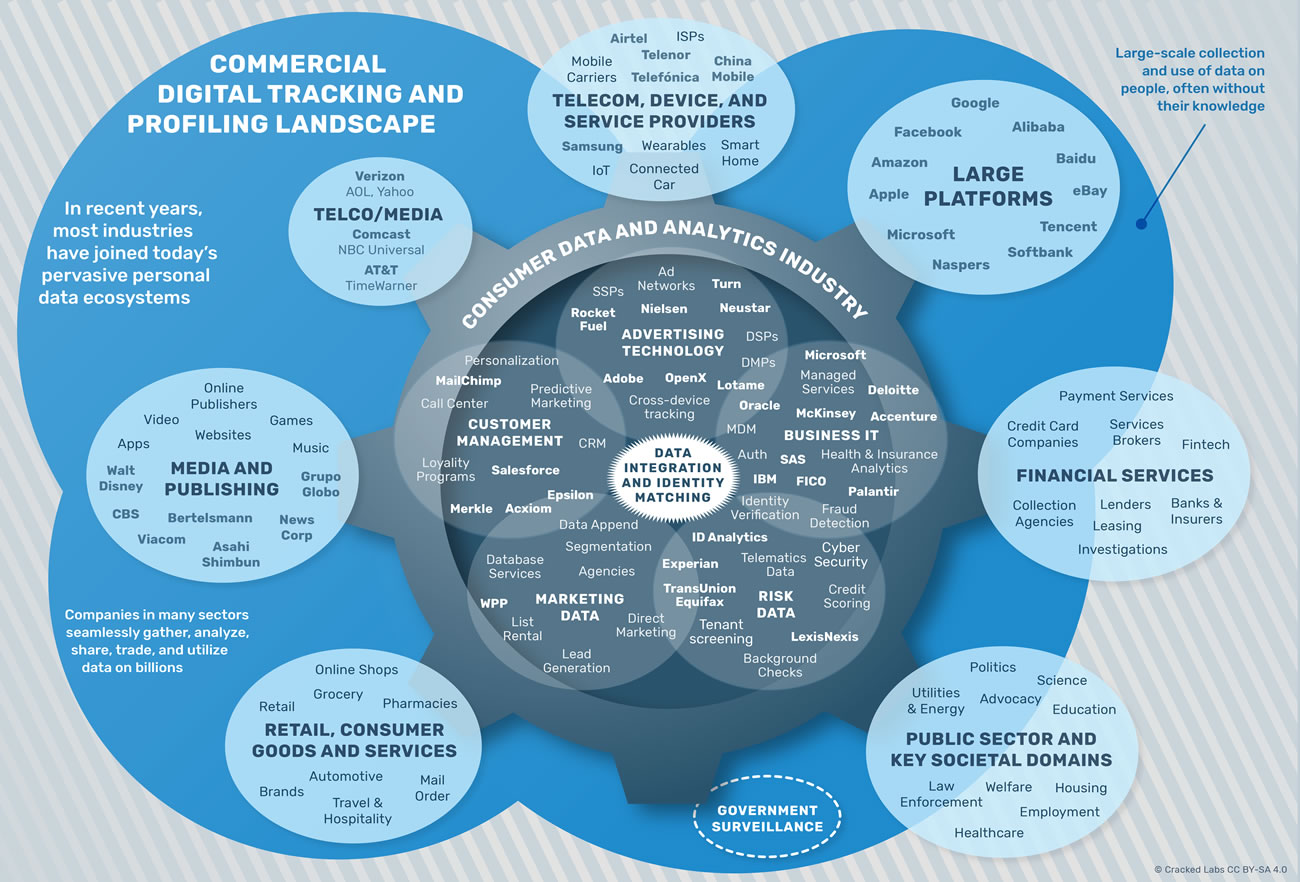

Google and Facebook, followed by other large platforms such as Apple, Microsoft, Amazon

and Alibaba have unprecedented access to data about the lives of billions of

people. Although they have different business models and therefore play

different roles in the personal data industry, they have the power to widely dictate

the basic parameters of the overall digital markets. The large platforms mostly

restrict how other firms can directly obtain their data; in this way, they

force them to utilize the platform’s data on users within their own

ecosystems and gather additional data from beyond the platforms’ reach.

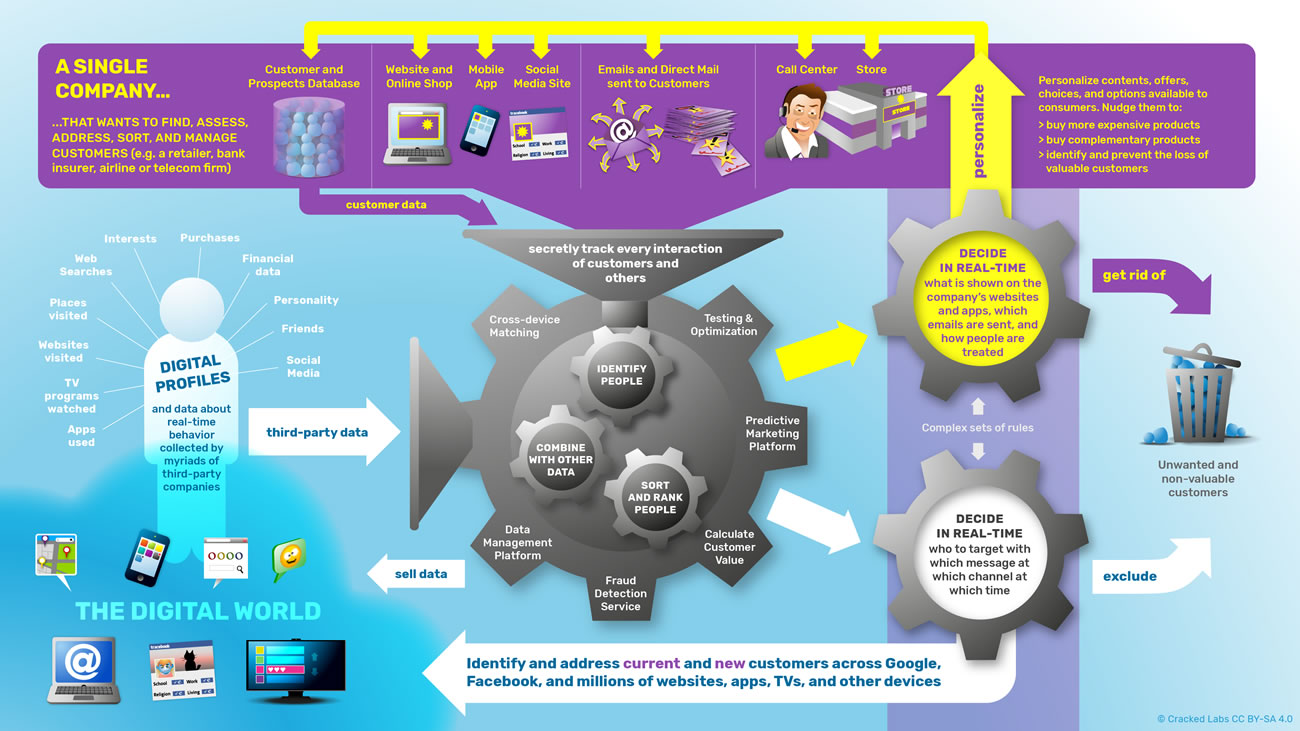

Although the large multinationals in

different sectors that have frequent interactions with hundreds of millions of

consumers are in a somewhat similar position, they not only acquire consumer

data collected by others, but often also provide data. While parts of the

financial services and telecoms sectors, as well as crucial societal areas

such as healthcare, education, and employment, are subject to stronger privacy

regulation in most jurisdictions, a wide range of companies has started to

utilize or contribute data to today’s networks of commercial surveillance.

Retailers

and other companies that sell products and services to consumers mostly also

sell data about their customers’ purchases. Media conglomerates and digital publishers

sell data about their audiences, which is then utilized by companies in most

other sectors. Telecom and broadband providers have started following

their customers through the web. Large companies in retail, media and telecom have

acquired or are acquiring data, tracking, and advertising technology firms.

With Comcast acquiring NBC Universal, and AT&T most likely acquiring Time

Warner, the large telecoms in the US are also becoming giant publishers,

creating powerful portfolios of content, data, and targeting capabilities. With

its acquisition of AOL and Yahoo, Verizon also became a “platform”.

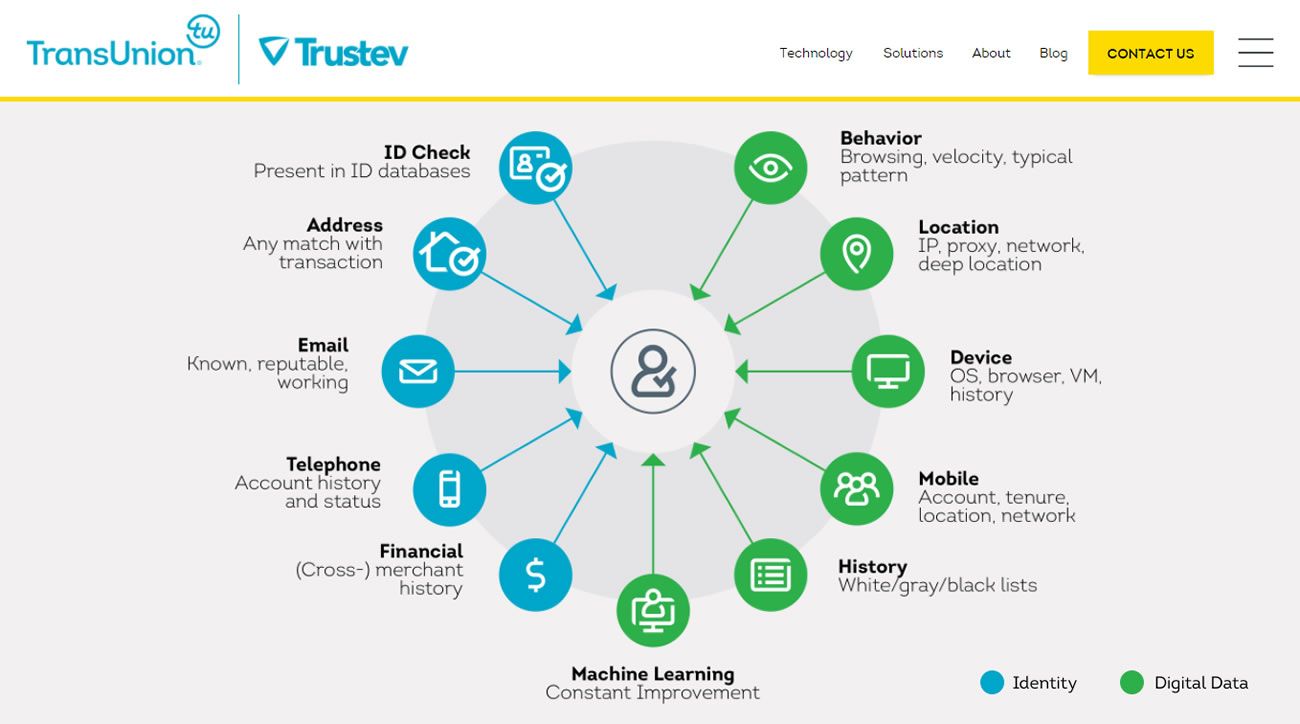

Financial institutions have long used data on consumers for risk management, such as

credit scoring and fraud detection, as well as for marketing, customer acquisition,

and retention. They supplement their own data with external data from credit reporting

agencies, data brokers and marketing data companies. PayPal, the biggest

name in online payments, shares personal information with more than 600

third parties including other payment providers, credit reporting agencies,

identity verification and fraud detection companies, as well as with the most

advanced players within the digital tracking ecosystems. While credit card

networks and banks have shared financial data on their customers with risk data

providers for decades, they have now started selling transactional data

for marketing purposes.

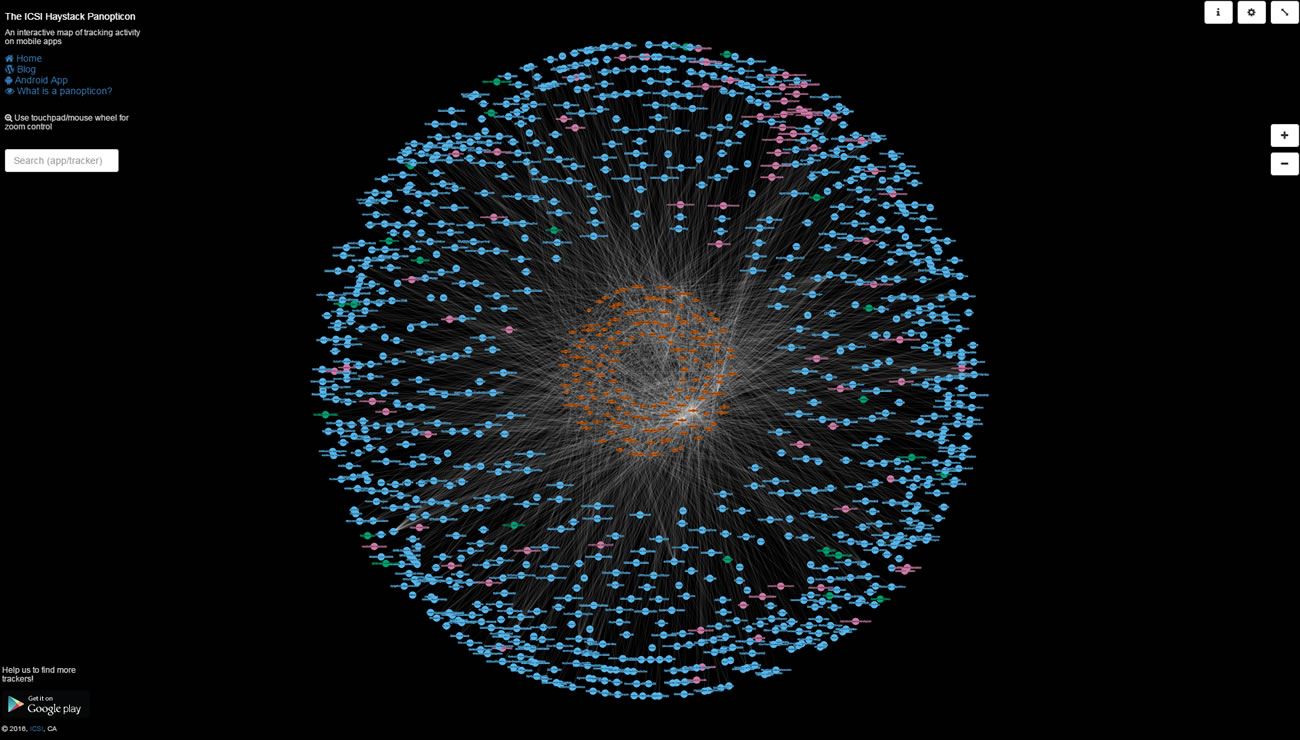

A myriad of smaller and larger firms

providing websites, apps, games, and other applications are closely

connected to the marketing data ecosystem. They use services that allow them to

easily transmit data about their users to hundreds of third-party services.

Many of them sell their users’ behavioral data streams as a core part of their

business model. Even more worryingly, companies that provide new kinds of

devices such as fitness trackers also seamlessly embed

services that transfer user data to third parties.

The pervasive real-time surveillance

machine that has been developed for online advertising is rapidly

expanding into other fields including politics, pricing, credit scoring, and

risk management. Insurers all over the world have started to offer their

customers programs involving

real-time tracking of behaviors such as car driving, health activities, grocery

purchases, or visits to the fitness studio. New players in insurance

analytics and financial technology predict individual health risks based on

consumer data, as well as the creditworthiness of individuals based on

behavioral data on phone calls or web searches.

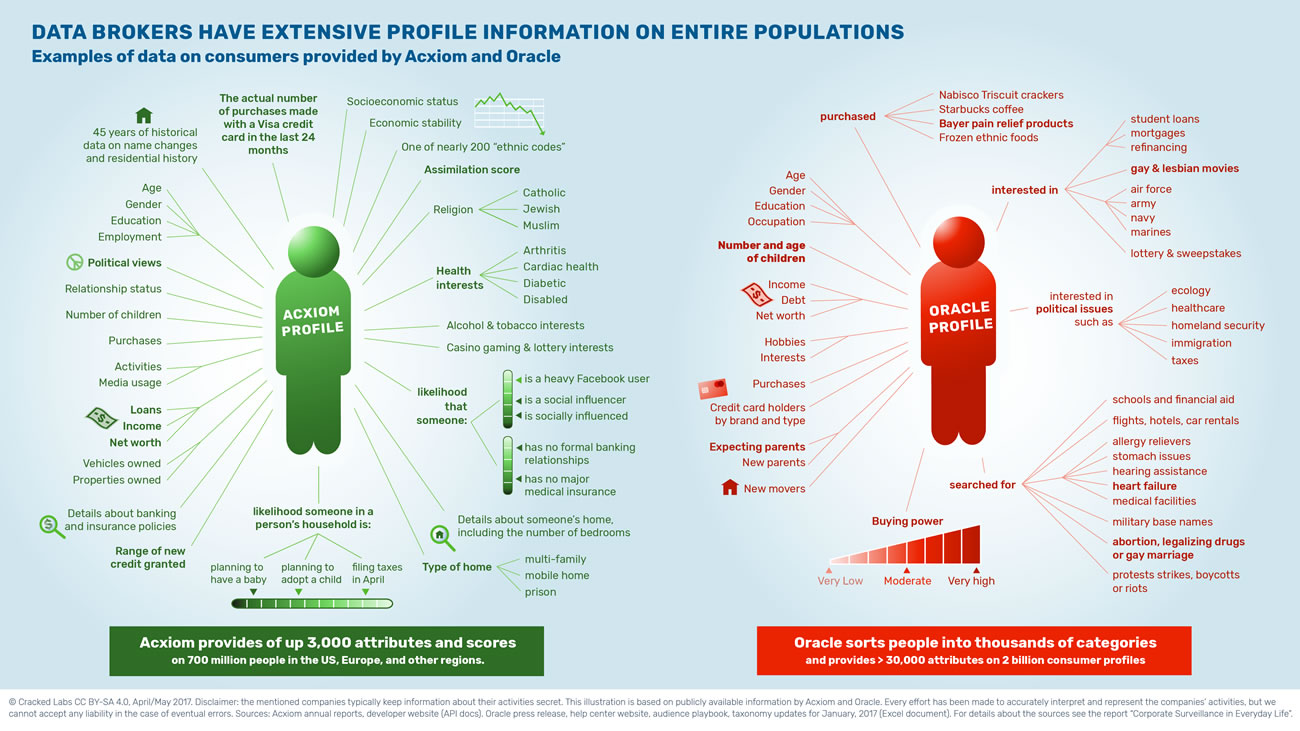

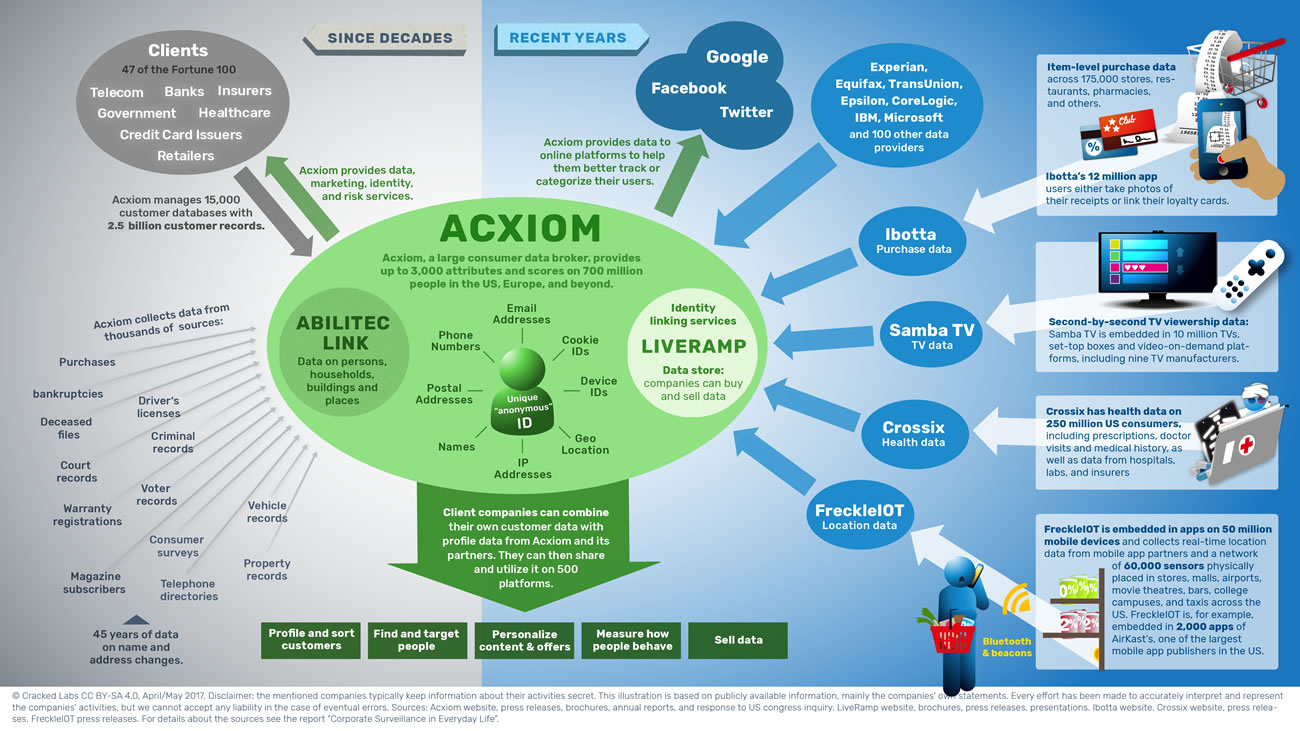

Consumer data brokers, customer management companies, and advertising agencies such as

Acxiom, Epsilon, Merkle or Wunderman/WPP play a major role in combining and

connecting data between platforms, multinationals, and the advertising

technology world. Credit reporting agencies like Experian that provide

many services in very sensitive fields such as credit reporting, identity

verification and fraud detection also play a major role in today’s pervasive

marketing data ecosystem.

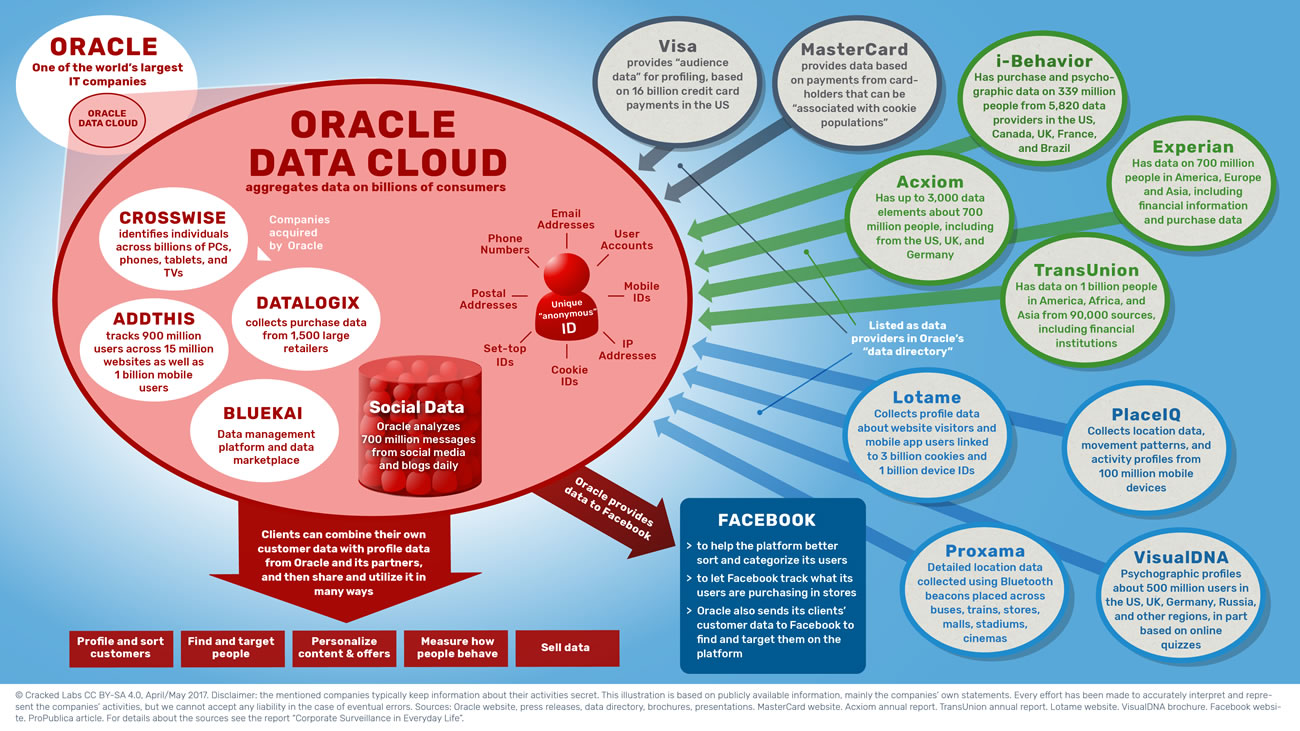

Particular large companies that provide data,

analytics, and software services have been named as “platforms” as well. Oracle,

a large database and business software provider, has become a consumer data

broker in recent years. Salesforce, the market leader in customer

relationship management that is managing the customer databases of millions of

clients, yet having many customers each, has acquired

Krux, a major data company connecting and combining data all over the digital

world. The software company Adobe also plays an important role

in profiling and advertising technology.

In addition, most major companies in business

software, analytics and consulting, such as IBM, Informatica, SAS, FICO,

Accenture, Capgemini, Deloitte, and McKinsey, or even intelligence and

defense firms such as Palantir, also play a significant role in the

management and analysis of personal data, from customer relationship management

to identity management to marketing to risk analytics for insurers, banks, and

governments.

X. Towards a society of pervasive digital social control?

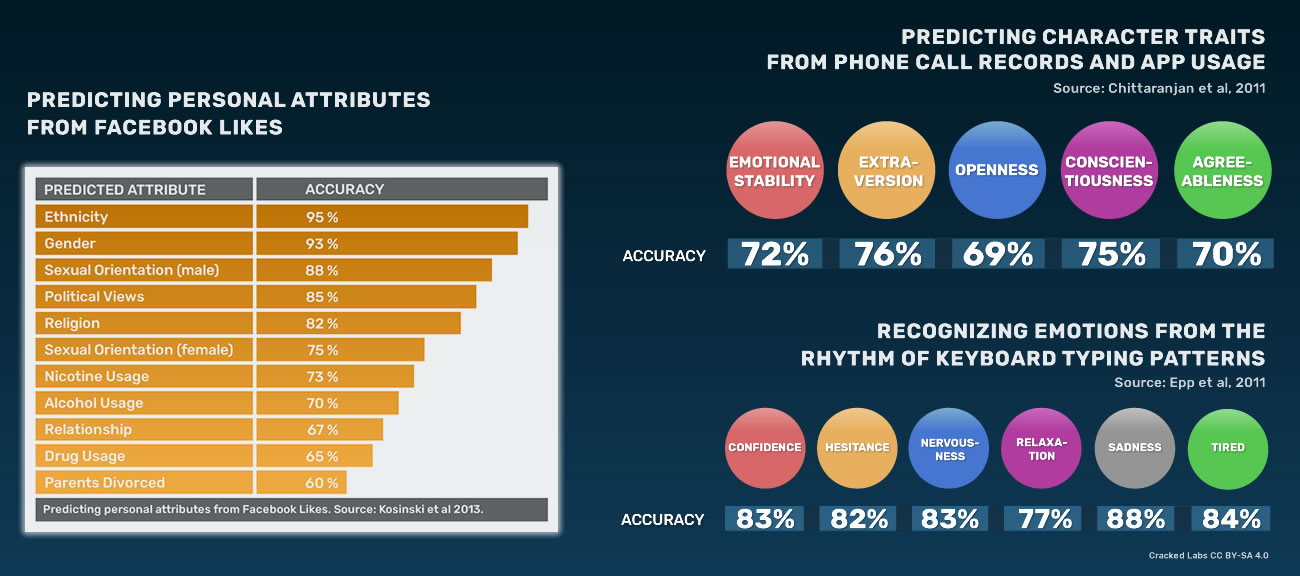

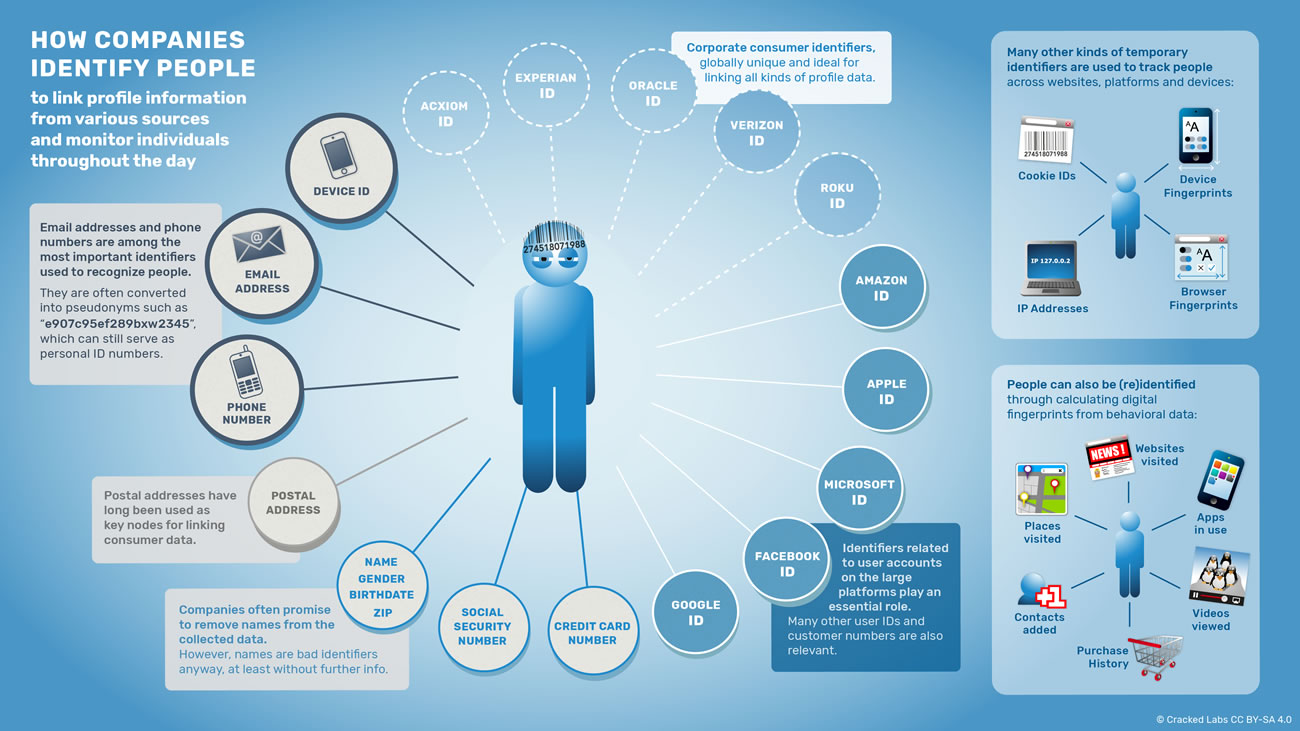

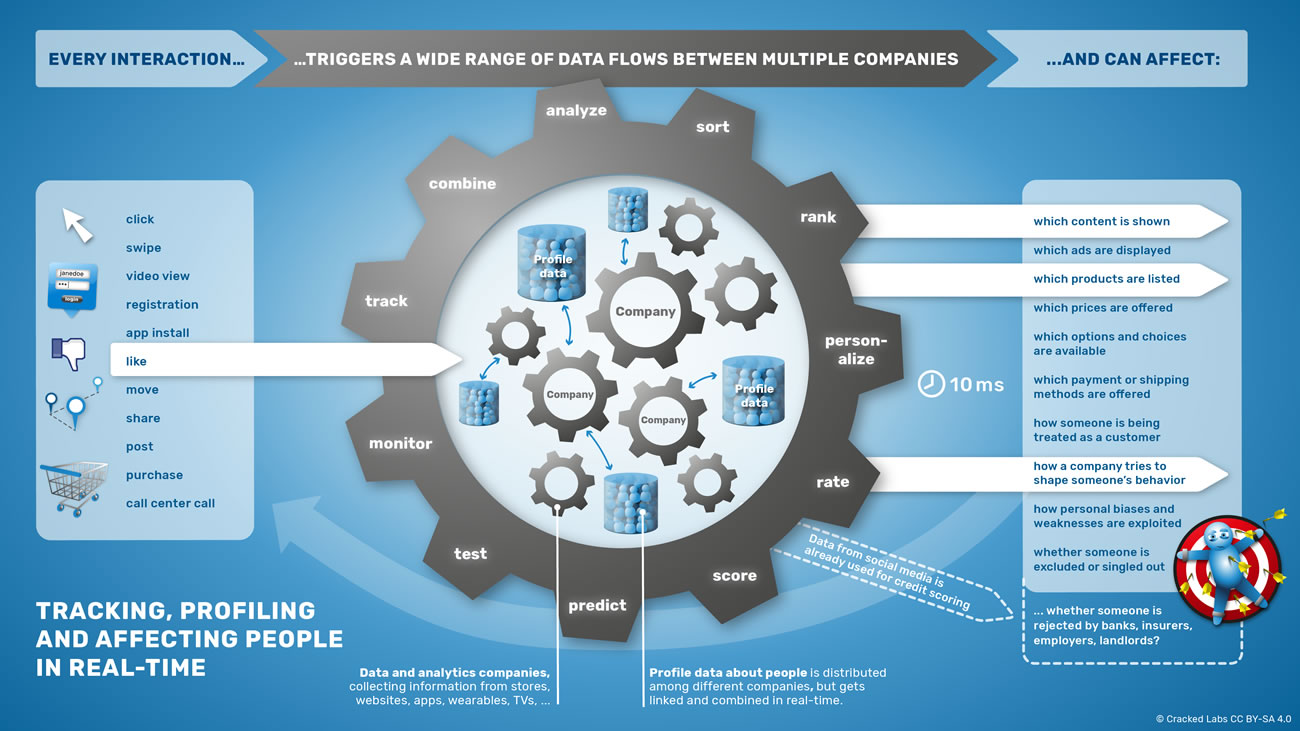

This report finds that the networks of

online platforms, advertising technology providers, data brokers, and other businesses

can now monitor, recognize, and analyze individuals in many life situations.

Information about individuals’ personal characteristics and behaviors is

linked, combined, and utilized across companies, databases, platforms, devices,

and services in real-time. With the actors guided only by economic goals, a data

environment has emerged in which individuals are constantly surveyed and

evaluated, categorized and grouped, rated and ranked, numbered and quantified,

included or excluded, and, as a result, treated differently.

Several key developments in recent

years have rapidly introduced unprecedented new qualities to ubiquitous

corporate surveillance. These include the rise of social media and networked

devices, the real-time tracking and linking of behavioral data streams, the

merging of online and offline data, and the consolidation of marketing and risk

management data. Pervasive digital tracking and profiling, in combination with

personalization and testing, are not only used to monitor, but also to

systematically influence people’s behavior. When companies use data

about everyday life situations to make both trivial and consequential automated

decisions about people, this may lead to discrimination, and reinforce

or even worsen existing inequalities.

In spite of its omnipresence, only the tip

of the iceberg of data and profiling activities is visible to individuals. Much

of it remains opaque and barely understood by the vast majority of people. At

the same time, people have ever fewer options to resist the power of this

data ecosystem; opting out of pervasive tracking and profiling has

essentially become synonymous with opting out of modern life. Although

corporate leaders argue that privacy

is dead (while caring

a great deal about their own privacy), Mark Andrejevic suggests that people do indeed

perceive the power asymmetries of today’s digital world, but feel “frustration

over a sense of powerlessness in the face of increasingly sophisticated and

comprehensive forms of data collection and mining”.

In light of this, this report focused on

the actual practices and inner workings of the contemporary personal data industry.

While the picture is becoming clearer, large parts of the systems in place

still remain in the dark. Enforcing transparency about corporate data practices

remains a key prerequisite to resolving the massive information asymmetries

between data companies and individuals. Hopefully this report’s findings will

encourage further work by scholars, journalists, and others in the fields of

civil rights, data protection, consumer protection, and, ideally, also of

policymakers and the companies themselves.

In 1999, Lawrence Lessig famously predicted

that left to

itself, cyberspace will become a perfect tool of control shaped primarily by

the “invisible hand” of the market. He suggested that we could “build, or

architect, or code cyberspace to protect values that we believe are

fundamental, or we can build, or architect, or code cyberspace to allow those

values to disappear”. Today, the latter has nearly been made reality by the

billions of dollars in venture capital poured into funding business models

based on the unscrupulous mass exploitation of data. The shortfall of privacy

regulation in the US and the absence of its enforcement in Europe has actively

impeded the emergence of other kinds of digital innovation, that is, of

practices, technologies, and business models that preserve freedom, democracy, social justice, and

human dignity.

On a broader level, data protection

legislation alone will not mitigate the consequences that a data-driven world

has on individuals and society, whether in the US or Europe. While consent and choice are crucial

principles to resolve some of the most urgent problems of intrusive data collection,

they can also produce an illusion

of voluntariness. Besides additional regulatory

instruments such as anti-discrimination, consumer protection, and competition

law, it will generally require a major collective effort to realize a

positive vision for a future information society. Otherwise, we might soon end

up in a society of pervasive digital social control, where privacy becomes – if

it remains at all – a luxury commodity for the rich. The building blocks are already

in place.

Further reading:

- A more comprehensive take on the issues covered

in the web publication above, as well as references and sources, can be found

in the full report, available as a PDF

download.

- The 2016 report "Networks of Control" by Wolfie Christl

and Sarah Spiekermann, which the current report is largely based on, is

available as a PDF download and as a printed book.

The production of this report, web materials, and illustrations was supported by the Open Society Foundations.